Kim Wahnke, December 2023

Fairy tales are one of the most well-known literary forms amongst children, and have occupied this space for centuries around the globe. With their simple forms and magical characters, they manage to appeal to a variety of children. Fairy tales are some of the most significant texts in influencing children and adolescents’ habits of thought and behaviours all the way into adulthood. They include first teachings about morals, empathy, understanding and peacebuilding.

Although their impact is well-known and they are often used in classroom settings and other educational contexts, fairy tales are barely mentioned in peace education theory. The interconnection between the study of fairy tales (Märchenkunde) and peace studies/ peace education is remarkably sparse. This fundamental lack is portrayed by both peace encyclopaedias having no entries between fairy tales and peace (Katz and Young, 2010), as well as fairy tale encyclopaedias being marked by an absence of peace-related entries (Ranke, 2016). Both disciplines do not acknowledge each other’s existence and there is little research that connects the two. The ways in which fairy tales, one of the most well-known literary forms, can be used for peacebuilding is therefore a mostly unexplored space in academia.

This report aims to change this and offer some insight into how fairy tales can be used to talk and learn about peace. It aims to shed light on what helpful or problematic narratives and ideas of peace can be found in fairy tales. Furthermore, it hopes to inspire educators to use fairy tales to explain peace and peacebuilding in more nuanced ways to children, and through that to help them foster and build peace themselves within different levels of society. Finally, it ties the insights together by exploring how peace education can be enriched through the introduction of fairy tales and provides inspiration for learning activities.

Definitions

A fairy tale as described in this report is a traditional children’s story that usually involves fantastic forces, imaginary creatures and magic (Merriam-Webster, 2019). They are characterised by interweaving the everyday and the wonderful, yet separating themselves from a claim to truth (Lüthi, 2005). This report includes not only folk fairy tales (Volksmärchen) but also literary fairy tales (Kunstmärchen) under this definition. While it will mostly be referring to the fairy tales of the Grimm brothers (“Kinder- und Hausmärchen”), an enlargement of the material, including fairy tales from other authors and cultures is encouraged. This definition of fairy tales sticks to traditional presentations in the form of orally or textually transmitted fairy tales. It therefore separates itself from modern fairy tales, which can be presented in the form of movies, series, interactive exhibitions, comics or computer games (Conrad, 2020). In terms of defining peace education, the report will be using the peace education definition from Peace Insight: “Peace education promotes the knowledge, skills and attitudes to help people prevent conflict occurring, resolve conflicts peacefully, or create conditions for [inner and outer] peace.” (Peace Insight, 2023).

Fairy tale content on peace

Most fairy tales do not focus on portraying violence and peace on a larger scale. Their emphasis is not on society at large, but instead on a single character that navigates their own journey through the world. War and armed conflict are rarely portrayed; instead, there is usually a single evil person set in opposition to a single good person (or group). Fairy tales usually don’t showcase any explicit peacebuilding activity between groups, but instead a singular hero learns about behaviour on a smaller scale (Geister, 2023b). The main characters are learning how to manage conflict with themselves or between others, not how to solve violence on a large scale. Most fairy tales do not mention peacebuilding as a task delegated to someone higher within a group (hierarchy) or as something out of reach, but instead make the main characters take an active part in it. This gives the children reading them a closeness to the topic that can lead to a development of agency and empowerment. Even in the rare cases where there is a larger conflict portrayed, the main characters are still directly involved in the process of peacebuilding, portraying it as something accessible and closely connected to people’s lives (Hiller, 2023).

Focusing on smaller scale peace, fairy tales teach morals and peaceful behaviour to their readers. The fairy tale transmits a moral message outside of providing entertainment (Erlidawati and Rahmah, 2022). The tales therefore convey important moral, religious, societal and family values. This is important in order for children to understand the environment they live in and appropriate behaviours within it (Lieberman, 1972). Fairy tale’s main characters often display behaviours and have values that are integral to peacebuilding: these include integrity, tranquillity, bravery, self discipline, and self-confidence, as well as love, compassion, respect, loyalty, dependability, sensitivity, kindness, friendliness, and justice towards others (Erlidawati and Rahmah, 2022). Oftentimes, the heroes make an effort to include social outliers in their lives (“The Old Man and the Grandson”1), help people in need (“Snow White and Rose Red”1) or teach us about basic skills and values for a life in society (“The Golden Key”1) (Hiller, 2023). The fairy tale therefore shows children ways to interact with others in an empathetic, kind and respectful way, therefore laying groundwork both for conflict-prevention and conflict-resolution, especially for small-scale peace.

The fairytale also has similar potential for teaching children a vision of individual peace rooted in ecological sustainable development. In fairy tales, animals, plants and other parts of nature often appear as helpers for the hero. The main character interacts with them in a way that shows their respect and appreciation for them (“Snow White”1). Often, one of the things that make the hero stand out is their special connection with nature and the way they are connected to it. Furthermore, the protagonist’s resourcefulness is often central to their success (“The Fisherman and His Wife”1). According to fairy tale expert Marieta Hiller (2023), nature and the environment are rarely presented as endlessly exploitable resources, but instead always limited in scope (e.g. a protagonist having only three wishes). The characters and readers are therefore encouraged to use the resources they have access to for the greatest good (Hiller, 2023). This shows a connection to the environment and to others based on respect, understanding and interconnectedness.

Different dimensions of peace addressed through fairy tales

Fairy tales can assume an important educational role, especially during key developmental shifts (usually ages 4-6) when children begin to understand both their own imperfections and that others exist outside them (Moskalenko, 2023). This births their first significance quest, according to Moskalenko (2023), forms a significant blueprint for behavioural patterns that children form and later (un)consciously repeat throughout their life. The developmental shift is often accompanied by disturbances for children. Fairy tales can help them consciously experience and gain a very basic understanding of their own emotions for the first time, potentially gaining an improved toolkit to later achieve inner peace. The core motives of fairy tales are timeless, they thematise “Urängste” (universal fears) that all children can relate to (Conrad, 2020). These universal childhood experiences are exemplified through fairy tales: an example of this is “Hansel and Gretel”1, which deals with the childhood fear of being left or abandoned by one’s parents (Geister, 2023b). The children who read these fairy tales identify with the characters and their fears, experiencing their problems and partaking in their journey towards solving the problem and self discovery (Geister, 2023b). The identification of the child with the character and their connection to the storyteller is further emphasised by most fairy tales being orally reproduced and being rooted within a tradition of recital in a family space (Mönckeberg, 1978). According to fairy tale expert Dr. Oliver Geister (2023b), reading a story that engages with deeply rooted childhood fears in a safe and loving environment can help children better deal with their emotions and fears and even lessen the fears. Unlike other teaching styles, reading fairy tales does not focus on the observation of behaviour or verbal instruction but instead, on learning symbolically and in connection to children’s emotions (Moskalenko, 2023). This is a unique and personal way of engaging with people’s emotions, potentially setting them up for improved understanding and regulation of their own emotions and dressing the pathway for inner peace. Fairy tales in this way have the potential for healing emotional conflicts within both children and adults (Bolton, 2016). Their possibility to advance and guide people towards inner peace is powerful. Therefore, the tales can often function as a catalyst for healthy emotional growth for children (especially those having suffered emotional disturbances) (Bolton, 2016).

Fairy tale settings, characters and events are unlike the ones in children’s lives and set in an absolute past; they are therefore perceived to have a different value. A connection persists between the readers and the characters’ emotions, but the distance allows them to experience them at a distance, often relating to others’ feelings and emotions for the first time. Children identify with fairy tale characters and feel their trials and triumph, emulating positive characters and avoiding behaviours and traits of negative characters in fairy tales (Moskalenko, 2023). They intimately connect with the moralities taught in fairy tales, often intuitively grasping it and applying it to their own lives, often leading to more considerate and peaceful behaviour. When readers resonate highly with a fairy tale, they may find their perceptions of values transformed and emotionally integrate certain characteristics within the tale, often ones that are conducive to their behaviour within groups (Bolton, 2016). Through this identification, children can acquire a range of behaviours, reactions and character traits. Therefore, children’s social behaviour is often scaffolded on fairy characters that were used as “dummies” for understanding basic behaviours and then applied to real-world scenarios. According to Moskalenko, these often form a baseline of our behaviours and can come out well into adulthood when people are faced with highly intuition-based decisions (Moskalenko, 2023). She later describes these latter situations as being mostly conflict situations, but they are similarly applicable to the high stakes and low control moral dilemmas that peacebuilding often involves. Therefore, the moralities and characters taught in fairy tales are deeply relevant for the behaviours of individuals in peacebuilding contexts.

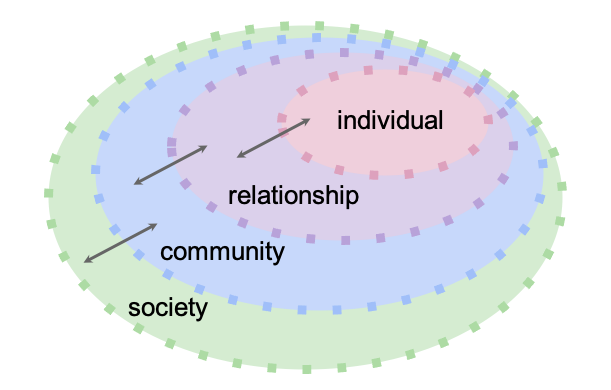

The obvious perspective on fairy tales in peacebuilding is the individual one: one child learning to understand their emotions, improving their inner peace and eventually improving their interactions in a close circle. Nevertheless, viewing storytelling as a phenomenon restricted to smaller scales of peace can often be reductive. There is a lack of understanding of individual peace perceptions influencing multiple layers of social circles and also the societal level. The socio-cultural model by Dahlberg and Krug (2006) aims to change this idea. The model includes the individual, relationship, community and societal scales (Dahlberg and Krug, 2006). It portrays the agency of the individual as well as accounts for their embeddedness within ever larger social circles (Unicef, 2022). Dahlberg and Krug (2006) use it for describing the endemic spread of violent actions through different layers of society. In the same way that violent narratives and individual small actions can contribute towards building a violent society, building peace on the small scales has the potential to reach audiences in larger scales. Therefore, an individual understanding peace in a different way has the potential to impact every layer of the model, up to the societal one. The porosity of the different layers and the arrows between them have been added to the Dahlberg and Krug (2006) model, aiming to further show the interaction between different layers.

Fairy tales are not only an individual endeavour. Reading them means reading the production of a rich history and tradition of oral repetition, only recently having culminated in a written production. Fairy tales form a part of cultural memory and can be considered a source of cultural history (Lüthi, 2005). According to Dr. Dickerhoff, president of the European Society for Fairytales, fairy tales are “living museums” that have the potential to preserve and distribute cultural heritage to people everywhere (Dickerhoff, n.d.). As pioneers of migration they traverse different cultures, adapting to each one and yet preserving their essence. Reading fairy tales from different countries and contexts can therefore help with forming improved cultural awareness and intercultural communication in children. In Europe particularly, fairy tales are very similar in their motives and characters; it is often their regional twist that connects the listener to the fairy tale (Dickerhoff, n.d.). Even when motives are culturally influenced, the stories are very often similar in their essence, being magical good-bad stories with a moral message (Waschkau and Waschkau, 2021). In hoping that countries around the world continue to grow together, interact and learn from each other, preservation of cultural specificity in fairy tales is just as important as the preservation of culinary or language dialects (Dickerhoff, n.d.). Learning and interacting with other cultures’ traditional fairy tales and comparing them with one’s own has the potential to further tolerance and create bridges for people across the globe. Improved intercultural understanding and interconnection can be of help in reducing stereotypes and promoting dialogue and communication as methods of conflict resolution. Furthermore, finding the similarities in fairy tales around the world can alert us to cross-cultural understandings and ways of visualising peaceful ways of living.

Fairy tales are especially powerful narratives for storytelling, being cultural tools that have reached millions of children in a variety of forms and that have transmitted their ideas of morality to very large audiences of people. The world’s current favourite fairy tales have been rebranded and therefore picked by children and caregivers for centuries, reflecting strong cultural preferences (Moskalenko, 2023). They can therefore be said to be “messages from the collective unconscious” and provide an important backdrop for connecting them with similarly universally resonating ideas: like peace (Isler, 2010). They set cultural rules and expectations for everyone, often being interrelated to standards of appropriateness and basic etiquette around the world (Moskalenko, 2023). The internalisation of fairy tales is therefore not a purely private phenomenon, but a socio-cultural and historical endeavour (Bolton, 2016). Since they are incredibly wide spread and well known (especially the most popular ones), they impact every single one of the layers of the model (Dahlberg and Krug, 2006). Children are part of smaller social circles, but also part of larger social circles and of society. Their ideas of peace, whose basics they have gained through influential narratives in their childhood, constitute part of society. Generations of children have been culturally conditioned through fairy tales, giving them a unique power of bridging tradition and modernity and having the potential of connecting different generations for the peace effort (Lieberman, 1972). The idea and hope is that peace education through fairy tales can subsequently reach and resonate with a variety of different children and adults and motivate them to act for peace. Following the model, even impacting one child’s perception of peace has the potential to lead to change in the entirety of our societal system.

Problems with using fairy tales for peace education

While fairy tales have a lot of power in creating peace and transmitting peaceful narratives in society, they also transmit other narratives which are often not viewed quite as positively. The tales are often strongly infused with Christian and patriarchal values and stances towards violence which can be a hurdle in using them for peace education. An incomplete list of this includes: gender roles, the centrality of marriage, violence, and the polarity of good and evil. A first and strongly critiqued issue within traditional European fairy tales is their reductive and outdated view on gender norms and marriage. The Grimm Brothers infused fairy tales with strong Christian values and rewrote stories to enforce patriarchal gender norms (Pfeifer, 2017). These stories therefore cast girls into stereotypical, reproductive gender roles and water down the agency of strong heroines in fairy tales orally transmitted by women (Pfeifer, 2017). The most popular and famous fairy tales reinforce narratives promoting the acculturation of women (Lieberman, 1972). This includes an emphasis on the value of beauty and of being chosen (by a man) as well as a discouragement of traits seen as “too bossy” for women including activity, ambition, strong-willingness and the pursuit of power (Lieberman, 1972). Millions of young girls are therefore encouraged to submit to men and to see their ideal behaviour as the most passive possible. Restrictive gender roles and the encouragement of passivity for half of the population are barriers to approaching peace in ways that are inclusive and further the participation of all. The centrality of (heterosexual) marriage further reinforces these gender norms, with boys actively winning kingdoms and princesses, while women are being “chosen” (Lieberman, 1972). In fairy tale terms, there is a triangle of value and importance connecting being beautiful, being chosen and getting rich (Lieberman, 1972). Even though marriage is very often presented as the final goal, married life is rarely shown (Lieberman, 1972). Not only does this show “being chosen” as the final goal of young women, it also misses out on an opportunity to show human relationships beyond the initial stages. Since fairytales show courtship as exciting and marriage as “the end”, children may develop a desire to constantly be courted, instead of engaging in meaningful relationships (Lieberman, 1972).

A similar critique concerns the outdatedness of the graphic and violent punishments in fairy tales. A lot of older literary fairy tales like Anderson’s are notorious for their cruelty and gruesome violence (Waschkau and Waschkau, 2021). Grimmish tales like “How children played slaughter with each other” have been criticised as being too violent for centuries, but even popular tales like “The Little Red Riding Hood”1 end with intense punishment instead of a reconciliation or a more mild punishment. The question arises whether every fairy tale is an appropriate children’s story (Lutkat, 2023). The harsh punishments are justified by a strict categorisation of characters into the camps of “purely good” and “purely evil”, with a very low chance of movement across these categories (Geister, 2023b). This lack of moral ambiguity can yet again be problematic for peace education. The goal is precisely not to see the other as “evil” and impossible to reason with but to encourage people to see other perspectives. The peace education bottom-line of the other person being worthy of respect and deserving humane treatment even through conflict does not seem to apply in fairy tales. This reductionist view does not only make most non-violent conflict-resolution systems redundant, but also portrays the other as “irredeemably evil”. Moral ambiguity is therefore central to peace education and yet rarely found in fairy tales.

Teaching fairy tales peacefully

While fairy tales, just like any literary form come with issues of their own, their problems are not impossible to be overcome and deal with. A lot of issues within the tales can be dealt with through an understanding of the fact that the fairy tale has no correct variant or interpretation: it has been reinterpreted again and again and can be understood in a different way in the current context (Salm, 2014). Reinterpretation and reimagination are parts of the fairy tale’s constant tradition of change. Even Jakob Grimm noted that “All fairy tales were set down long, long ago, in infinite variations, which means that they are never definitively set down.” (Rizzardi, 2019). The living narratives underwent countless changes as they were told, retold and written down (Pfeifer, 2017). According to Pfeifer (2017), in order to help children understand the depth of some topics that fairy tales have trouble explaining, they don’t need a feminism lecture, but an awareness of the polyphonic traditions of fairytales. This includes an understanding that each story is shaped and edited to their liking by the teller, that there are multiple versions of each story and therefore no real or original one.

Giving children the option of looking at different versions of one story that they particularly like, or the option to look at a variety of stories in general allows them to combine different elements and understandings of the characters into narratives that promote creativity and agency. As Pfeifer (2017) says, “Elsa’s dress could go well with combat boots, her crown with a skeleton costume”. Often, this allows children to draw parallels or explore differences between traditional and modern fairy tales and identify (or don’t identify) with them in different ways (Conrad, 2020). Through this open format, children have the possibility to explore fairy tales inside and outside of their immediate cultural context and have the possibility to explore different and modern fairy tales that are more progressive but less well known (Lutkat, 2023). To use fairy tales for peace education would therefore include (as far as possible) following the desires and impulses of the child; listening to the fairy tale that they connect most with, then looking at different variations of this and seeing which one resonates with them the most (Schwarz, 2017). Often children show their connection to one or multiple fairy tales, by being active and involved listeners, speaking the lines with the narrator, clapping, excitement or stomping along (Lutkat, 2023). They are then not solely consuming but reusing the pictures of the fairy tales in their imagination and their play (Mönckeberg, 1978). Letting children guide the discussion and the tales can help add to fairy tales producing inner peace for them (Schwarz, 2017). Children wanting to hear one fairy tale over and over again often connect to a specific aspect of the fairytale, relating it to their own problem or strongly identifying with one of its characters (Horn, 2011). Keeping to the same fairy tale but still giving the child the possibility to explore its different forms can help with their development of inner peace without stunting creativity or focusing on harmful ideals in the process.

Suggested activities:

Aim: create an awareness of the polyphonic traditions of fairy tales and highlight that there is no one correct narrative to them.

- Introduce children to different fairy tales from different cultures, authors and time periods

- Act out a fairy tale instead of reading it2

- Go to a theatre rendition of a fairy tale

- Rewrite a fairy tale: Take a tale and retell it using a familiar setting, local animals and personal customs3

- Have children think about how the story would be different if they could decide what happens: What would change? Who would the characters be and what would they do?3

This kind of approach can also be useful in approaching violence within fairy tales. While Grimmish and Western tales are often marked by cruelty, the same cannot be said about Eastern, Japanese and Inuit fairy tales (Waschkau and Waschkau, 2021). While the darkness and evilness of fairy tales can give children and adults pictures for their feelings and fears, the original Grimmish fairy tales need to be treated with care (Lutkat, 2023). Once again, one needs to follow the intuition and the enthusiasm of the child when approaching he tales. If children are hypersensitive for example, it is worth it to stick to less graphic descriptions in fairy tales and ones that focus on non-violent plots (Waschkau and Waschkau, 2021). With children that are older, the task of engaging with moral ambiguity can be undertaken, advancing ideas of dialogue and of empathy and questioning the motives of the villain as just purely evil (Bolton, 2016).

Even if children only enjoy or connect with violent fairy tales, that is usually not a reason for worry. Fairy tale experts like Oliver Geister (2023b) suggest a more symbolic reading of fairy tales, to understand that children often don’t see the violent acts in fairy tales as what they are, but as a defeat of a personification of evil and therefore as justified. Fairy tales can be viewed similarly to dreams, as pictorial representations of the unconscious and therefore as offering purely symbolic advice (Isler, 2010). The burning of the witch in “Hansel and Gretel” therefore does not refer to the actual killing of an elderly woman but instead to a defeat of evil. Similarly, marriage and inheriting a kingdom at the end of a fairytale often refers to personal growth or a deeper understanding of the self (Geister, 2023b). It can also refer to a new prince and with him a new philosophy of life overtaking “the old way of doing things” under the old king (Isler, 2010). Analysts like Geister (2023b) and also Lutkat (2023) encourage us to understand fairytales on the symbolic level: it is not a witch in the forest in the child’s mind, but a reflection of their own experiences, longings, wishes and fears.

Suggested activities:

Aim: Let children better understand and connect with the villains of fairy tales, create an understanding of the “other” not being purely evil.

- Did you feel sorry for the villain? Why or why not? What could the hero have done differently? (example: Rumpelstilzchen)4

- Interview the villain: how do they feel?, why did they do what they did?, do you understand them?2

- Write a letter to a fairy tale character, think about what you think of their behaviour, of their way of interacting with others (hero or villain)2

Even though fairy tales are often given the title of “outdated”, fairy tale expert Oliver Geister believes that they have the potential to further media-competent-action in children. Unlike other educational methods, fairy tale reading is less restrictive towards creative approaches, relying on aesthetic over efferent reading. Efferent reading is used in most educational settings and consists in reading a text to extract information from it for later use (Bolton, 2016). There is an expectation of the child having understood the details of the text. Aesthetic reading on the other hand gives children the possibility to savour the experience of reading and to construct their own meaning from their personal associations with the tale (Bolton, 2016). Reading fairy tales in a way that is aesthetic as opposed to efferent therefore helps emphasise the emotional connection of children towards the tale, creating the space for personal memories, associations and feelings to guide the way the text is understood (Bolton, 2016). Aesthetic reading is a transaction between the text and the reader, leading to the text being both a stimuli as well as the potential groundstone for a contemplative response. This kind of text interaction is therefore often seen as therapeutic or meditative (Bolton, 2016). This has the potential to fuse emotions with memories in a harmonious way, helping children to understand their emotions in a deeper way and guide them towards inner peace.

A central part of fairy tales that grounds them within peace education is their optimism and their tendency to give a sense of agency and empowerment to their readers. They give a hopeful impulse to the often disparate realities of peace-making and shed light on the potential of the individual in changing lives for peace. Some analysts, like Conrad (2020) go as far as to say that it is not morality but optimism that is the central feature of fairy tales. According to them, what fairy tales give children is a guarantee that one can succeed as long as one has confidence (Schwarz, 2017). They claim that a rewarding, positive life is within one’s reach despite adversity if the child is courageous enough to embrace the search for it and actively engages in finding it (Rizzardi, 2019). The fairy tale therefore encourages embracing activity, risks and struggles in order to work towards peace instead of being discouraged by hopelessness or fear.

Suggested activities:

Aim: Putting the emphasis of an experience of reading, connected to emotions and memories more than to the contents of the tale.

- Pay attention to the child to see if they are enjoying a tale, if not, read a different tale

- Peaceful activities while reading the tale: braid hair while reading “Rapunzel”1, connect reading “The Star Talers” to a visit of the Planetarium, connect reading “The Wild Swans”1 to a visit of the botanical garden2

- Questions after reading the tale: How did you like it? How did you feel? Who is your favourite character? What did you not like? Would you like to live in that fairy tale? What would you do if you could live in that fairy tale? What emotions are you feeling after reading this? What images does this create in your mind? What actions do you want to take after reading this?3

Fairy tales stimulate the imagination of children by being suggestive, posing questions and only indirectly expressing solutions (Schwarz, 2017). They are therefore a stimulus for children to create their own ideas and lives. This creative approach can be heightened when children are read the tales without the accompanying pictures, so that they can instead imagine the heroes themselves and let their creativity take over. Storyteller Everhard Drees agrees with this, claiming that he rejects costumes while reading fairy tales, in order to let the children form their own visuals based on the content (Geister, 2023a). The tales often tap into people’s creative energies which helps in solving problems in all situations of life. Visualising the characters, places and solutions themselves lays the groundwork for one of the core values of fairy tales, which is empowering children to imagine and think for themselves (Pfeifer, 2017).

Suggested activities:

Aim: provide stimuli for children to engage their creativity and create their own solutions.

- Draw core things and places of the tale without having the description in front of them2

- Stop at certain spots in the fairy tale and ask the child how they would continue it2

- Bring character into a modern setting (What do they look like? What are they wearing? What are they doing?)2

- Glue different things into a collage and let the children explain how it connects to the fairy tale2

- Create a fairytale museum: What exhibits, what can you smell, feel, taste? Which objects are there? Are there guided tours?2

More stories for forming different kinds of peace

Most traditional fairy tales including peaceful themes, morals and ideas within them do not directly mention the concept of peace. Ideas of peacebuilding are present, but not described as peaceful. Yet, a lot of modern fairy tale adaptations as well as fairy tale-adjacent children’s stories do mention peace more directly or clearly, labelling it as such and directly engaging with larger scales of peace as well as conflict. In order to provide a different mix of ideas on peace and conflict, engaging with stories that fit these themes of peace and label them directly as such could be advisable.

Giving children a voice

Understanding and listening to the perspectives of others, especially those affected by conflict is an important pillar for peacebuilding. In current adaptations, like the animated UNFairy Tales, it is refugee children whose voices are centred (Unicef, 2016d). The childish aspects of their stories are overtaken by elements of war and displacement that invades these children’s lives (Unicef, 2016b). This turns them into nightmares – ‘unfairy tales’ (Tabak and Carvalho, 2019). Their unsettling endings are clearly not fairy tale finishes, showing the deviations from normal childhood and the vulnerability that accompanies this (Unicef, 2016a). The tales are a great example of letting people speak who do not have the platform to speak themselves, without talking over them. As Sherinian says “We all know what it is like to be a child, but we need to get better at communicating the realities of what refugee children face” (Unicef, 2016c).

Drawing attention to a conflict or injustice

An example of the usage of a fairy-tale-adjacent story to draw attention to existing injustices is Nadine Gordimer’s anti-apartheid fairy tale called “Once upon a time”. Her piece of work not only uses literature to change mentalities on an injustice, but also aims to make people aware of their own unjust behaviours (Rizzardi, 2019). Her story centres on the violence that the fear of the other can create, focusing on apartheid as an example. The dead child is portrayed as the ultimate cost of this violence, exclusion and racism through the securitisation of a white family under the apartheid regime (Rizzardi, 2019). The mother’s fear of the “looters and rioters” outside entering never comes true, instead the defense mechanism (razor wire) ends up being “evil” and killing her child. Not only does her story draw attention to a current injustice, but it also has an “upside-down mirror” spin on the clearly defined roles of good and evil within fairy tales (Rizzardi, 2019). It perverts securitisation due to fear of the others as the thing that actually diminishes security in the end.

Showing hope or pockets of peace within a conflict

The fairy tale-esque story “Where the Poppies Now Grow” by Robinson and Impey (2014) focuses on the transitions of life from before the conflict all the way through and until the end of it. The aim of the book is mostly remembrance of the horrors of the First World War and an appreciation for times of peace (Robinson and Impey, 2014). However, throughout the entire time it is the friendship of the two main characters that guides the story and leads to all characters making it out alive to experience peace time. The story has a similar rhythm to a lot of fairy tales, characterised by rhymes and repetitions and therefore very accessible to children. This linguistic element additionally shows the main focus on the two main characters and their friendship. Their friendship is portrayed as a pocket of peace through the horrors of war, as well as through times of peace (Robinson and Impey, 2014).

Presenting the hero as a peacebuilder

In the story “Peace Lily” by Robinson and Impney (2018) the focus is on the character of Lily and her role as a nurse in the First World War. Her commitment to helping and caring for others is a central aspect of the story and contributes to the characters well-being and their happy ending. Even before her activity as a nurse, her letters to her friends are described as “letters of hope”. The end of the war is rhetorically connected to Lily’s birth, just as prophesied by her parent, who believed that his daughter would eventually become a symbol of hope for others (Robinson and Impey, 2018). Letting children engage with a variety of different perspectives of what it means to be a peacebuilder can broaden their perspective and motivate them for action. This is especially true for even Lily’s small actions (like her letters of hope) being considered, since these are accessible and easy to practise even for children and show them the universality of the possibility of becoming a peacebuilder.

Conclusion

This report aims to show the usefulness of considering fairy tales as a medium for teaching peace as well as a tool for the wider visualisation of peace. It hopes to inspire educators to use fairy tales not only for connecting children to tradition and teaching them basic behaviours but to use this opportunity to introduce inner and outer peace into the conversation. Peace in fairy tales is visualised in more personal and small-scale ways, focusing on inner and small conflicts. While it has a less direct focus on portraying peace and war on the large scale, its small-scale depictions of peace can help children visualise peace both within themselves (understand their emotions better and move towards more inner peace) and in small groups (teaching children about understanding others, empathy and basic behaviours). Furthermore, the fairy tale has the potential to impact not only individual but also communal and societal understandings of peace through influencing various layers of the socio-ecological model. This is the case since fairy tales are one of the narratives that are most widespread amongst children and whose narratives are reused in a variety of different contexts. The report therefore proposes to utilise the outreach of these stories by connecting them to peace education for children. Even the problematic aspects of the fairy tales can be outweighed by positives if the materials are used in a way that children can deeply connect to them and form their own connections to them. The report furthermore suggests that alternative children’s sources, including modern fairy tales and fairy tale-esque literature can be used to provide a more comprehensive insight on peace education.

Hopefully, this report can start off a closer interrelation between the disciplines of fairy tale studies and peace education. As an important medium of storytelling, fairy tales have the power to be used for peace, especially with more material available on how to use them in correct ways for furthering the efforts of peace education. In the future, more input and writing on peaceful fairy tales could advance the discipline even further and provide more materials.

Endnotes

1Grimmish fairy tales from https://www.projekt-gutenberg.org/grimm/khmaerch/khmaerch.html

2Educational materials from https://www.goethe.de/lrn/prj/mlg/miu/mak/deindex.htm

3Educational materials from https://teachpeacenow.com/peace-tales-lesson-plan/

4Educational materials from https://www.schule-bw.de/faecher-und-schularten/sprachen-und-literatur/deutsch/unterrichtseinheiten/prosa/kurzprosa/maerchen/grimm/verlauf_maerchen.pdf

Bibliography

Bolton, E. (2016). Meaning-making across disparate realities: A new cognitive model for the personality-integrating response to fairy tales. Semiotica, 2016(213). doi:https://doi.org/10.1515/sem-2015-0141.

Conrad, M. (2020). Was ist ein modernes Märchen? FAU Erlangen-Nürnberg. Available at: https://www.fau.de/2020/07/news/wissenschaft/was-ist-ein-modernes-maerchen/ (Accessed: 9 Dec. 2023.

Dahlberg, L.L. and Krug, E.G. (2006). Violence a global public health problem. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 11(2), pp.277–292. doi: https://doi.org/10.1590/s1413-81232006000200007.

Dickerhoff, H. (n.d.). Europäische Märchengesellschaft Präsident. Available at: https://www.unesco.at/fileadmin/Redaktion/Kultur/IKE/IKE-DB/files/Maerchenerzaehlen_Expertise_Heinrich_Dickerhoff.pdf (Accessed 10 Dec. 2023).

Erlidawati, E. and Rahmah, S. (2022). The Educational Values in Fairy Tale Cartoon Film. JETLEE : Journal of English Language Teaching, Linguistics, and Literature, 2(1). Doi: https://doi.org/10.47766/jetlee.v2i1.203.

Geister, O. (2023a). Märchenpädagogik. www.maerchenpaedagogik.de. Available at: http://www.maerchenpaedagogik.de/index.php (Accessed 7 Dec. 2023).

Geister, O. (2023b). Visualising Peace with Oliver Geister.

Goethe Institut (2020). Märchenhaft – zwölf Ideen für den Unterricht. Märchen – Goethe-Institut. Available at: https://www.goethe.de/lrn/prj/mlg/miu/mak/deindex.htm (Accessed 8 Dec. 2023).

Grimm, J. and Grimm, W. (2023). Kinder- und Hausmärchen. 16th ed. www.projekt-gutenberg.org. Projekt Gutenberg DE. Available at: https://www.projekt-gutenberg.org/grimm/khmaerch/khmaerch.html (Accessed 10 Dec. 2023).

Hiller, M. (2023). Visualising Peace in Fairy Tales (Interview).

Horn, K. (2011). Der eine war aus Gold, der zweite aus Silber, der dritte aus Kupfer – Wiederholung und Variation im europäischen Volksmärchen. Available at: http://www.symbolforschung.ch/files/pdf/K_Horn_Wiederholung_im_Maerchen.pdf (Accessed 1 Dec. 2023).

Isler, G. (2010). The New Pope and the Animals: On the Spirit of Nature in Fairytales and Popular Legends. Psychological Perspectives, 53(3), pp.280–312. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00332925.2010.501216.

Katz, N.H. and Young, N. (2010). The Oxford International Encyclopedia of Peace. Oxford University Press eBooks. Oxford University Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/acref/9780195334685.001.0001.

Landesbildungsserver Baden-Württemberg (n.d.). Unterrichtseinheit Märchen – Schüler bearbeiten Märchen und verfassen eigene Texte. Available at: https://www.schule-bw.de/faecher-und-schularten/sprachen-und-literatur/deutsch/unterrichtseinheiten/prosa/kurzprosa/maerchen/grimm/verlauf_maerchen.pdf.

Lieberman, M.R. (1972). ‘Some Day My Prince Will Come’: Female Acculturation through the Fairy Tale. College English, 34(3), pp.383–395. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/375142.

Lutkat, S. (2023). Sabine Lutkat: ‘Märchen gehören nicht in die Kleinkinderecke’. Deutschlandfunk Kultur. Available at: https://www.deutschlandfunkkultur.de/gewalt-und-rollenklischee-wie-zeitgemaess-sind-maerchen-dlf-kultur-a8075a5f-100.html.

Merriam-Webster (2019). Definition of fairy-tale. Merriam-Webster. Available at: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/fairy-tale.

Mönckeberg, V. (1978). Über die Kunst Märchen zu erzählen. Europäische Märchengesellschaft. Available at: https://www.maerchen-emg.de/video-audio/video (Accessed 9 Dec. 2023).

Moskalenko, S. (2023). Fairy Tales in War and Conflict: The Role of Early Narratives in Mass Psychology of Political Violence. Peace Review, 35(2), pp.1–10. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10402659.2023.2181662.

Peace Insight (2023). Peace education. Peace Insight. Available at: https://www.peaceinsight.org/en/themes/peace-education/?location&theme=peace-education.

Pfeifer, A. 2017, Making Peace With Princesses, New York, N.Y.

Ranke, K. (2016). Enzyklopädie des Märchens Online. De Gruyter. Available at: https://www.degruyter.com/database/emo/html#dbLemma (Accessed 5 Dec. 2023).

Rizzardi, B. (2019). ‘Once Upon a Time’ by Nadine Gordimer: A Fairy Tale for Peace. Le Simplegadi, (19), pp.43–52. doi:https://doi.org/10.17456/simple-127.

Robinson, H. and Impey, M. (2014). Where the poppies now grow. Strauss House Productions.

Robinson, H. and Impey, M. (2018). Peace Lily. Strauss House Productions.

Salm, K. (2014). Das Märchen ist längst nicht tot. Schweizer Radio und Fernsehen (SRF). Available at: https://www.srf.ch/kultur/gesellschaft-religion/gesellschaft-religion-das-maerchen-ist-laengst-nicht-tot (Accessed 4 Dec. 2023).

Schwarz, A. (2017). Die Bedeutung der Märchen für Kinder. Gesellschaft für Familienorientierung. Available at: https://cms.familienorientierung.at/blog-post/die-bedeutung-der-maerchen-fuer-kinder/ (Accessed 8 Nov. 2023).

Tabak, J. and Carvalho, L. (2019). Responsibility to Protect the Future: Children on the Move and the Politics of Becoming. brill.com. Available at: https://brill.com/display/book/9789004379534/BP000008.xml?language=en (Accessed 9 Dec. 2023).

Teach Peace Now (2016). Peace Tales Lesson Plan: Using folktales to talk about peace. Teach Peace Now. Available at: https://teachpeacenow.com/peace-tales-lesson-plan/ (Accessed 8 Dec. 2023).

Unicef (2016a). ‘Unfairy Tales’ – True stories of refugee and migrant children inspire UNICEF to launch – #actofhumanity global initiative. Unicef Papua New Guinea. Available at: https://www.unicef.org/png/press-releases/unfairy-tales-true-stories-refugee-and-migrant-children-inspire-unicef-launch

Unicef (2016b). Watch Unfairy Tales: some stories were never meant for children. Unicef Ireland. Available at: https://www.unicef.ie/stories/watch-unfairy-tales-some-stories-were-never-meant-for-children/ (Accessed 5 Dec. 2023).

Unicef (2016c). Watch Unfairy Tales: True Stories From Refugee Children. Unicef Ireland. Available at: https://www.unicef.ie/stories/watch-unfairy-tales-true-stories-from-refugee-children-on-the-move/ (Accessed 4 Dec. 2023).

Unicef (2016d). Watch: Ivine (14) fled Syria, with her cherished pillow. Unicef Ireland. Available at: https://www.unicef.ie/stories/watch-ivine-14-fled-syria-with-her-cherished-pillow/ (Accessed 8 Dec. 2023).

Unicef (2022.). BRIEF ON THE SOCIAL ECOLOGICAL MODEL. Unicef. URL: https://www.unicef.org/media/135011/file/Global%20multisectoral%20operational%20framework.pdf.

Waschkau , A. and Waschkau, A. (2021). WildMics Special #54 – Märchen. www.spektrum.de. Available at: https://www.spektrum.de/podcast/welchen-stellenwert-haben-maerchen-in-unserer-modernen-gesellschaft/1882378 (Accessed 11 Dec. 2023)