An interview between Visualising Peace members Tao Yazaki, Zoe Gudino and Alice König:

Tao, Zoe: What is Responsible Debate?

Alice: On a daily basis at the moment, I think we all see examples of debate that we might call ‘irresponsible’ – in politics, in some parts of the media, and online. Discussions that are based on poor information, or even lies. Ad hominem attacks on people we disagree with. Inflammatory language that creates more heat than light. Politicians who deride each other for ‘doing a u-turn’, when in fact changing our view in response to new information or altered circumstances can be a positive thing! The list could go on. This kind of debate and discussion polarises people and drives conflict. It is a very poor way approach to communication, it makes it harder – not easier – to resolve challenging issues, and it polarises people, making discussion and debate all the more difficult in future.

It is easy to get demoralised by this – but we really need to address our habits and cultures of debate if we want to solve the big challenges which our society and world are facing. So back in 2019, I got together with three colleagues in the Young Academy of Scotland – Matthew Chrisman, Peter McColl and John O’Connor – to explore ways to promote more responsible debate. We were not interested in getting everyone to agree with each other, or in taking passion and argumentation out of debate. What we wanted to find out was how we could get better at discussing contentious issues with a sense of shared purpose – how we could continue to debate and even disagree, while finding common ground and exploring solutions collaboratively.

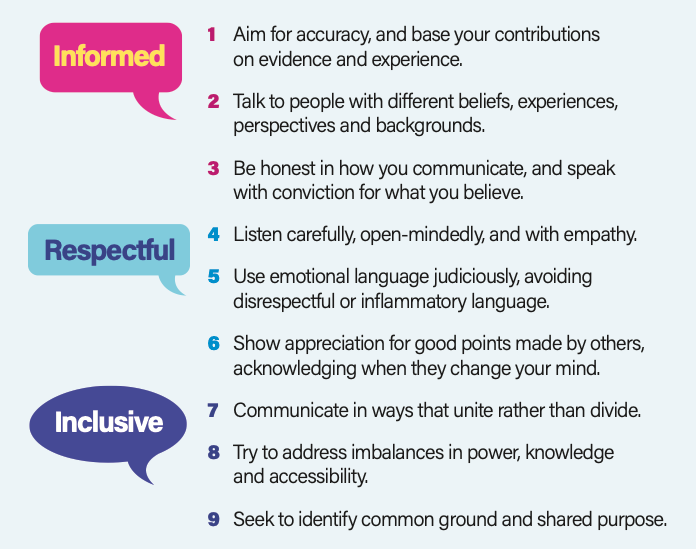

We embarked on a two-year research and consultation process, talking to people in broadcast media, on social media, politicians, academics, and people whose voices have often been marginalised in debates. We then drew on their input to create the Charter for Responsible Debate: a set of 9 principles, which we hope will promote more informed, respectful, inclusive and collaborative debate. It pays attention to how we listen, as well as how we speak; to how we acknowledge or respond to other people’s input; and to how we address imbalances in power, knowledge and accessibility. Above all, it advocates for approaches to debate that aim to unify rather than divide (even when profound disagreements remain) and it underlines the benefits of focusing on common ground and finding shared purpose.

As our report underlines, we don’t see the Charter as a definitive set of principles which will always work in all contexts – but more as a starting point for getting people thinking and talking about better and worse habits of debate, hopefully in ways that ultimately improve our shared debating culture. In a nutshell, Responsible Debate is reflective debate, which is outcomes-focused – looking ahead to solutions and seeking common good, rather than debate that tries to score points or ‘win’ the argument on the day.

Tao, Zoe: What are some of the motivations behind the creation of the Responsible Debate charter?

Alice: The Responsible Debate project was inspired in part by just how awful the debates had been – on both sides – around the UK’s Brexit referendum in 2016, and also by the ‘post-truth’ politics that very populist politicians like Donald Trump have promoted and benefited from. More generally we were also motivated by an awareness that individual societies and the human race have some very big challenges to address over the coming decades. Climate change is a global problem; but some people still deny the science behind it, or play politics over possible solutions. And climate change is one of several factors driving an uptick in both conflict and forced displacement or migration, which are huge humanitarian issues that some politicians and players in the media are weaponizing for self-interest (votes, sales, etc). The rapid evolution of social media and digital technologies such as AI looks set to transform life as we know it – in some positive ways, but potentially also with disruptive and dangerous consequences. In short, we are wrestling with some huge issues that affect the whole planet – and we need to get much better at collaborative discussion and debate if we are to address them effectively.

Tao, Zoe: How can Responsible Debate be used to build peace?

Alice: Sustainable peacebuilding processes (whether at home, in school, in local communities, or between states or armed groups) require diplomacy, mediation, active listening, the careful use of language, inclusion of diverse voices, slow thinking, iterative dialogue, sense-checking, fact-finding, learning journeys, the acknowledgement of wrongs, expressions of sorrow and regret, and – above all – a willingness to find common ground and shared purpose, despite differences and historic injustices. We see this style of debate modelled all too rarely in public spaces and in the online world. But this is exactly the kind of communication which the Responsible Debate Charter promotes.

In fact, the Charter not only aligns with the kinds of communications that we need in post-conflict situations but also with behaviours that we need to adopt if we want to prevent conflict from breaking out in the first place, or re-emerging in the wake of previous violence. Take, for example, Principle 2 in the Charter (‘talk to people with different backgrounds and perspectives’), which can break down divides and reduce in-group/out-group mentalities and polarisation; or Principle 4 (listen open-mindedly), which can help us be more receptive to different viewpoints; or Principle 8 (‘try to address imbalances in power’) which can ensure that we are more inclusive in our interactions; or Principle 1 (‘aim for accuracy’) which can prevent misunderstandings and build trust.

We are not saying that it’s easy, but we do think that responsible debate can play a significant role in promoting peace between individuals and communities.

Tao, Zoe: What is the greatest challenge to fostering Responsible Debate?

Alice: Bad actors. They are not a new phenomenon: for centuries, even millennia, influential people have distorted the truth for their own interests, misrepresented others, stirred up hostility with inflammatory language, set groups against each other via polarising rhetoric, attacked individuals rather than making progress on challenging issues, and generally used their voices for self-interest rather than the common good. Today, of course, broadcast media can carry those voices a very long way; and digital technologies have been harnessed to carry them even further. All sorts of bad actors who would not have reached us in the past are now online influencers with millions of followers, and social media bots are designed and deployed to shape discussions thousands of miles from their developers. These are not just challenges to responsible debate; they are challenges to global order, the security of states and communities, and to us as individuals – not least because they can impact our inner peace. It’s easy to feel overwhelmed by the sheer scale of the challenge, but we can’t afford to give up; so our best option is to try to infuse more responsible debate into our real and online worlds.

Tao, Zoe: What specific benefits do you see responsible debate having as an approach to the topic of social media and peacebuilding?

Alice: I think that reflecting on responsible debate can help us to explore ways of using social media more productively to promote peace – and it also underlines the vital importance of doing that, to push back against at least some of the ways that social media can drive conflict.

Social media has some really problematic features, as we know: people can debate with each other as very one-dimensional personas, algorithms keep us communicating within bubbles, short tweets and memes don’t lend themselves to nuance or complexity, extreme views tend to get more likes and shares, there is not enough regulation of mis- or disinformation, and so on…

These features of social media are not exclusive to the online world; they are extreme versions of problems that we often find in in-person debates. The word ‘debate’ itself is very combative – it is about ‘fighting things out’ – and traditional models of debate promote very competitive, win-lose styles of discussion, with speakers taking sides, reasserting their fixed positions, trying to score points off their opponents. Those listening are often encouraged to get into tribes, to get behind one particular viewpoint and oppose the another, sometimes with votes where the winner takes all. This style of debate encourages lots of the same problems that we see on social media: eye-catching headlines, rhetoric over substance, quick-fire responses, a disregard for accuracy, personal attacks, and worse.

By contrast, the 9 principles in the Charter for Responsible Debate encourage us to slow debate down, to check that we have understood what we think we have heard, to empathise with people taking different sides, to seek out different experiences and opinions from our own, to take care over language, and to notice the impacts of language on others, to see changing our minds as a positive thing, to notice and address inequalities and marginalisation, and to prioritise collaboration over competition.

If we have these ground rules in mind in any kind of debate, whether online or in person, we are likely to make more progress towards positive outcomes and collaborative problem-solving; and that is what our goal should really be, not winning an argument. So employing and experimenting with Responsible Debate principles to discuss the role of social media in peacebuilding not only helps us to think through the challenges (and opportunities) of online communication but it can also get us much further along the road of developing new methodologies, finding solutions to problems and making positive progress. As I have said, social media and other digital technologies are very powerful forces in the world today, with the ability to influence how people think and behave; so we can’t just leave them to bad actors. We have to get stuck in, and find ways to use them better, for vital work like peacebuilding; and that means thinking hard about how we can do this collaboratively, not debating whether or not to.

That is exactly why the Visualising Peace project is experimenting with different formats of responsible debate, as part of our research into the role of social media in peacebuilding. We can learn a lot about the topic from oppositional models of debate, but we can also learn a lot from more collaborative forms of debate, and from informal approaches – like our Chatty Monday coffee and cake event – that adjust traditional power imbalances, get us to rethink how we define experts and expertise, and widen access to these important conversations.

Tao, Zoe: How do you see Responsible Debate evolving in the future?

Alice: When my colleagues and I launched the Charter for Responsible Debate in 2021, our hope was that it would not only be adopted by politicians, media professionals, and organisations like universities and parliaments (to encourage more reflective debate in those spheres) but also that ordinary people might try out different principles in the classroom, workplace, around the dinner table, in email correspondence, and so on. (We have included some ‘try it out’ suggestions in our report.) It is intended to be something that everyone can experiment with – and we think that the more people who engage with it, and talk about it, and think about it, the better our shared habits of debate might become. In particular, we hope that it will contribute (alongside other initiatives) towards a move towards more informed, respectful, inclusive and collaborative debating culture. My colleagues and I have recently founded the Centre for Responsible Debate, and we have a number of projects underway, including some work on hate speech, the right to protest, and the thorny issue of non-platforming. But my own biggest focus over the next couple of years will be the connections we can make between responsible debate, conflict prevention, conflict resolution and conflict transformation: how responsible debate can contribute to personal, interpersonal and international peace.