Among other projects, we have been researching trends in peace education across different sectors and settings. Despite the enormous benefits of supporting young people to learn and think critically about peace and peace-building, many students still spend more time studying war than peace.

We have been surveying teachers, pupils and curriculum designers to find out more about current practice and future potential in subjects like history, English literature, art, drama, philosophy, religious studies, human geography, and sustainable development. We have also been exploring the role of educational experiences such as debating clubs, remembrance events, mindfulness training and peer mentoring in developing young people’s understanding of peace and peace-building.

Based on our findings, we have been developing some pilot workshops and teaching resources, to explore different methods and media for integrating critical peace studies into different educational settings. As well as supporting teachers to engage with relevant peace pedagogies in their subject areas, we are interested in helping education planners (in schools, museums, NGOs, etc) to connect different aspects of peace education – from teaching techniques to enhance inner peace to lessons on geopolitical peace-building.

Please click here to be directed to our developing set of ‘Teaching Resources‘.

Below, you can read a report containing some initial findings from our survey of teachers, plus some reflections on method, authored by Joe Walker. Joe has also recorded a fascinating presentation on the role of emotion and trans-rationality in peace education, with some follow-up bibliography suggestions in our Visualising Peace Library.

In this blog you can find a report by Otilia Meden, outlining the preliminary findings of her study into young people’s experiences of peace education in Argentina, Denmark and the UK. Otilia is particularly interested in the connections drawn in peace education between inner and outer peace, which connects to her wider research on inner peace. Her findings pose important new questions and research avenues for the development of contextually and culturally adapted peace education.

Research overview – by Joe Walker

- How is peace currently taught and understood in formal schooling in the UK and beyond?

- How do the International Baccalaureate Curriculum and the Scottish Curriculum for Excellence formulate and implement peace education and the values, norms, and attitudes that this education conveys?

- How does school ethos and culture influence the conception and teaching of peace in formal schools; and how does peace education in turn influence the culture and ethos?

Theory

The study of peace education takes as its founding principles, the work of Johan Galtung and his conceptions of structural violence and positive peace (Bermeo 2022). The work of Galtung is seminal in peace education, and joins other prominent authors in the subject, especially Jacques Rousseau and Paulo Freire. As Synott (2005) explains, the work of Rousseau in his thought on child development in Émile as the result of socialisation; along with the work of Freire in understanding learners as social, collective, and political in nature, produced the modern academic understanding of what peace education should look like in formal settings. Synott’s other insight, that is employed both explicitly and implicitly throughout this lesson plan, is the splitting up of peace education into “education about peace” and “education for peace” (Synott 2005, 12). Education for peace involves instilling the knowledge and attitudes needed to live peacefully (Brantmeier 2011), rather than merely teaching the facts about peace as a military or political entity. Bevington, Kurian, and Cremin (2019, 156) discuss the overlap between peace education and citizenship education, noting that citizenship and peace ‘both have human fulfilment at the heart of their endeavors’. Curricula such as the Scottish Curriculum for Excellence (CfE) are based around citizenship education, and therefore it is important to establish the implicit connections with peace education present.

Teachers are able to foster the transformative agency (Bermeo 2022, 462) necessary for challenging structural violence in society. The field of educational peace research (Bajaj 2015) highlights the reflexivity in teaching by recognising its role in the promotion of certain values, attitudes and norms in the local community and society at large. Reflexivity allows for teachers to speak about their experiences in honest and intricate ways, enriching the results of this study and allowing us to better understand the performance of the learning resources that we have developed. The role of teachers in peace education, as Brooks and Hajir (2020, 13) describe, is to internalise the specific models and behaviours needed for peaceful living. Educators must respond to violence in their roles, especially in places with more relaxed laws around firearms, such as the US. Therefore, the teacher’s understanding of peace as living peacefully with one another must be inculcated from the initial teacher training onwards. In education for peace, there is also a sense that the teacher learns alongside the students, and so the content of lessons should reflect this.

The curriculum is perhaps equally important in this regard. If teachers are the facilitators of peace education, then the curriculum is that which is being facilitated. The curriculum must ‘establish and sustain non-violent societies’ (Synott 2005, 12). The current curricula, such as the Scottish CfE do contain some elements of a broader conception of peace. Standish and Joyce (2016) detail the aspects of peace present in the CfE. The authors find that well-being, as emotional, mental, social, and physical, is comprehensively addressed in the curriculum, whilst there is also recognition of the importance of peer dialogue and collaboration. However, other attributes such as mediation, and environmental and gendered aspects of peace, are either limited or absent from the curriculum. In their work on connecting peace education and citizenship education, Bevington, Kurian, and Cremin (2019) discuss how a more complete citizenship/peace education involves centring gender and nature, as well as a recognition of multifaith teachings. This may involve moving away from a universalist approach to peace education, towards something more dialogical (Hajir and Kester 2020).

The work of Cremin, EchavarrÍa, and Kester (2018) details how a transrational approach to peace education can advance these aims, by including a holistic perspective through mobilising ‘several dimensions of the self’ other than the rational one advocated by Western peace education. Transrationality emerged from Wolgang Dietrich’s work on his theory of Many Peaces (Dietrich 2012), and brings together energetic, moral, modern, and postmodern aspects of peace; in doing so going beyond the rational view of peace as security and the binary of good vs evil towards a peace that engages with the emotional and spiritual aspects of what it means to be human (Dietrich 2014). Cremin and Archer (2018) discuss transrationality in direct relation to peace education, noting how modern and moral peaces; peace as relational security and peace as justice in a binary sense; are dominant in formal schooling. Transrational peace education would retain these conceptions of peace, but also add an understanding of energetic peace (the integration of body, mind heart and spirit) and postmodern peace, as local and contextual in its conception of truth.

This first section of research deals less with the specifics of the curriculum, and more on how each curriculum is applied in the classroom and the experiences of the teachers who teach it. Investigating how the curriculum is instigated means investigating the praxis of peace education – the fusing of theory and practice. Several of the authors cited in this section highlight the importance of praxis (Bermeo 2022; Synott 2005; Bajaj 2015). As important as theory is to peace education, it is the practice of delivering it that advances the field, and curricula is the method by which this education is practised.

There is also a close connection between the curriculum and school culture & ethos when it comes to teaching and learning about peace. The importance of social-emotional learning, conflict resolution, and multiculturalism in education, as discussed above, are fostered by inclusive school cultures that are central in shaping norms, values and attitudes in the local community and beyond (Brooks and Hajir 2020, 5). Brooks and Hajir (2020, 20) advocate a “culture of peace” in formal schools – an ethos that ‘aligns with the main values and principles of peace’. School culture is vital because it plays such a fundamental role in shaping the local community. Local disputes and attitudes are influenced by the socialisation of the population towards particular conceptions of conflict resolution and structural violence, and therefore school culture should be central in changing these aspects. Peace education is about the ‘skills necessary for living peacefully’ (Bermeo 2022, 462), and many of these skills are fostered through co- and extracurricular activities that are set by the school leadership, who are therefore responsible for enforcing the school culture & ethos as a whole (Brooks and Hajir 2020, 12).

Methodology

The research undertaken in this project was based on a mixed-methods methodology that employs both quantitative and qualitative data gathering. There are several reasons for this. The first is that the relatively small scope of the research and resources available make the study unsuitable for relying solely on the collection on quantitative data, but there is still some utility in collecting some limited data-points so that the results of this experiment can be more contextually useful in comparison to the results of the other investigations undertaken in this lesson plan. The second reason is that mixing the quantitative and qualitative means that binary answers can be expanded upon to explore nuance and establish the thought and reasoning behind complex social phenomena such as the ones being explored here. Peace education acts at the level of culture and society, as well as in formal educational institutions, and must be investigated as such.

There are two methods employed in this project. The first is an online survey that has been circulated via social media and existing professional and academic networks to target as many teachers as possible. The purpose of the survey is to provide contextual information for the second method described below, but also to provide a baseline for the other sections of this document, by collecting the opinions of teachers on the current state of peace education in formal education. The survey is designed to provide data relating to each of the sub-questions that were posed above. The first few questions of the report are used for gathering demographic data so that the results of the survey can be analysed by region/curriculum/type of school/etc. The next set of questions deal mainly with the main research question, in terms of how peace is broadly conceptualised within formal educational institutions. Then, the survey poses several questions related to the curriculum and its implementation, as well as school culture, before finally directly addressing the other sections of this research document and pedagogical innovation. The survey is linked here.

The second method employed by this project was a semi-structured interview. This method involves a one-on-one interview with a member of staff at as Scottish school teaching the Scottish Curriculum for Excellence. The participant for this interview is involved in the teaching of peace, as an Religious and Moral Education teacher at secondary level.

Utilising a semi-structured interview allows for the asking of both closed- and open-questions (Adams 2015). This method therefore builds on the survey detailed above in trying to maximise the amount of information available given the small sample size. The semi-structured interview format allows enough structure for studying the research questions, whilst also leaving space for interviewees to offer new meanings to the focus of study (Galletta 2013, 24). There is room in the interview process for following up on unanticipated responses (Frances, Coughlan, and Cronin 2009, 310), which is important in researching a nuanced and complex subject such as peace education.

Semi-structured interviews should follow a basic structure, albeit one that is flexible enough to respond to the interview situation. As such, the structure for this interview has been divided into several parts that relate to the research questions above. The first section poses several questions relating to the teaching of the interviewee, beginning with several simpler demographic questions designed to develop the rapport needed for this type of one-on-one interview (Dicicco-Bloom and Crabtree 2006). The second section is themed around the interaction between the teacher and the curriculum they teach, the third is about the school culture and ethos, and the final section directly engages with the comic, peace journal and questions of pedagogy found in the other sections, especially the connections to be made between sociocultural and personal peace. The structure detailed below provides an overview of the questions likely to be asked, with the order indicating their importance in the event of time restrictions.

The Interview Structure

Section 1: Personal Teaching Experience

1. Several demographic questions related to place of work, subject[s] taught, position within the school etc.

2. What do you think of when you think about peace?

3. Do you think peace is taught well enough at [your school]?

4. What about in your specific subject?

5. What methods do you mainly use when you teach in general, and teach about peace more specifically?

6. Do you notice a difference between how different genders learn about peace, or if not, in more general learning?

Section 2: Curriculum Experience

1. How do you think peace is conceived in the curriculum that you teach?

2. Do you think there are some areas of the curriculum that have different conceptions of peace? Do you think some of these conceptions undermine the way you teach peace in your classes?

3. How much attention do you pay to the higher-level goals in your curriculum, for example about what kind of students the curriculum aims to foster?

Section 3: School Culture

1. How important is the school culture and ethos in your everyday teaching?

2. Do you think that the school culture is important when teaching about peace?

3. Do you think school culture is equally/more important than the curriculum in some ways?

4. How much do you think peace is involved in the extra-curricular activities that your school offers?

5. Has there been a conscious effort to promote the school culture through extra-curriculars?

6. Are there any extra-curricular activities that promote self-awareness and/or personal & inner peace? Do these concepts figure into the school culture and ethos at all?

Section 4: Our Project

1. Have you ever taught using similar methods as the ones we use in our lesson plan? How did it go?

2. What do you think of our methods, are they useful/practical? Do you think they improve students’ understanding of peace?

3. Do you think there’s scope in your teaching for making connections between different kinds of peace in your curriculum like we have in this lesson plan?

4. Do you personally, or the school staff as a whole, employ a particular pedagogy when teaching?

5. Do you think pragmatism in teaching is more important than any particular theory of how learning should be done?

These questions are, as mentioned above, flexible in their ordering, and follow-up prompts will be asked if unexpected answers are provided or if the interviewer seems merit in pursuing a particular avenue of questioning.

Results

Firstly, the survey results. There were 23 respondents to the survey overall. The survey was dispersed via online message boards, through Visualising Peace Project members, and through the pre-existing network of educators that Dr König possessed. The number of respondents is slightly on the lower parameter from which to draw generalised conclusions, which may be due to sector-wide disruption in UK teaching throughout the lifespan of this survey, as well as the general difficulties in collecting data from the public. The teachers who did respond were mainly secondary teachers, with 8% of respondents teaching at primary level. Subjects taught included Modern studies, geography, maths & science and classics, with the largest percentage of educators teaching English (30%), followed by History (22%). The vast majority of respondents taught in Scotland, but there were also responses from the United States, Western Australia, and Europe. 74% taught at state schools, and the Scottish Curriculum for Excellence was the most popular curriculum taught.

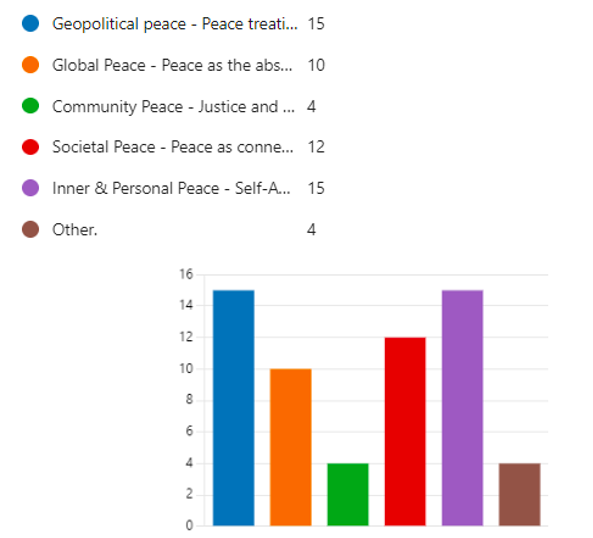

Moving onto the substantive questions; first of all, the word “calm” was the most popular response to words associated with peace (57%). Interestingly, only 9% of respondents associated the word “war” with peace. Figure 1 shows the response to question 9. Of interest here is the high level of inner & personal and societal peace that is currently taught, as well as the low level of community peace (justice and cooperation at more local levels). The teaching of inner & personal peace aligns with the work of Standish and Joyce (2016) in identifying the comprehensive coverage of wellbeing in the Scottish CfE, and it is encouraging in the context of Peace Education that peace is being viewed more broadly in schools in this fashion. There is also evidence for a limited flexibility for educators in choosing where, when, and how to teach peace, although many also note that the curriculum in later years is inflexible and exam-driven. This response was also common for question 13.

Figure 1: A graph of the different types of peace taught in respondent’s schools by response rate.

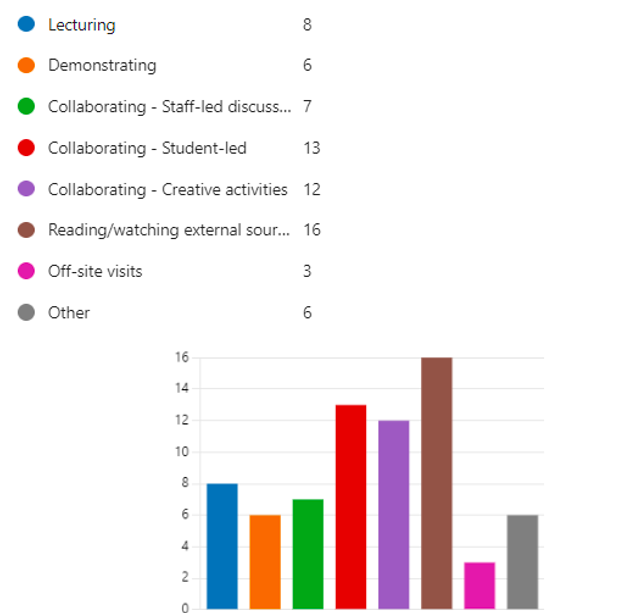

In terms of teaching methodology, traditional lecturing and demonstrating methods were less popular than collaborating and reading/watching external sources, as Figure 2 demonstrates. This again illustrates how many of the aspects of Education for Peace are already present within formal schooling, albeit not directly under the banner of Peace Education. Added to this, many of the responses to question 17 expressed a willingness to connect geopolitical peace with conflict resolution and inner peace, despite this currently being difficult due to time and curricula constraints. These responses point to a general willingness from the survey respondents to broaden peace teaching within their schools, but the responses to question 18 clearly indicate that they are not being given the knowledge or skills to carry this out, with 81% or respondents answering that Peace Education did not form part of their initial or subsequent training.

Figure 2: A graph showing the teaching methods of respondents in teaching peace, by response rate.

The semi-structured interview took place with a teacher of Religious and Moral Education working in the Highlands of Scotland using the CfE. This interview was arranged through the interviewee’s response to the online survey, and the participant was not connected to the Visualising Peace Project previously. The participant expressed an interest in Peace Education that began during his time at university and subsequent postgraduate studies, but during teacher training, the participant stated that ‘there’s nothing to do with peace … they didn’t do anything about peace’. This reflects the responses of others in the online survey, and perhaps points to a general lack of Peace Education training for teachers.

The participant was then asked about peace in the curriculum, especially in relation to the “character education” that the interviewee had mentioned in his previous answer. The focus on character education and values of figures such as Gandhi and Martin Luther King is emblematic of this focus on global citizenship that is the centre of the CfE, but it is certainly possible to see, as referenced above, that citizenship education can be linked explicitly to Peace Education. The participant noted how peace was not an explicit part of Religious and Moral Education course that dealt with peace; “they should have a box with specific targets about peace”. The participant stated that there was one lesson at the National 5 level where pacifism is taught, but this is directly related to warfare.

The participant elicited a great willingness to teach more about peace, especially as the school had received Ukrainian refugee students, and the participant felt that local students were unaware of the context and ramifications of receiving conflict refugees, especially as he felt that divisive language about immigration and indeed the rhetoric of figures such as Andrew Tate is reaching his students, and the curriculum is ill-equipped to combat this. Despite this, the participant did note some level of flexibility in choosing what is taught, especially in the opportunity to engage further with the Visualising Peace Project’s lesson plan.

As in the online survey responses, the interview participant highlighted the health and well-being aspects of the curriculum as areas where peace characteristics were being taught, albeit not explicitly. Other colleagues were mostly unaware of the opportunities for Peace Education but were similarly willing to engage with the Visualising Peace Project when informed, again indicating a latent interest about Peace Education among educators. Further, when asked about the importance of school culture, the participant noted a willingness from senior staff to engage with the Project and Peace Education more widely, stating that, “if there’s no support from the seniority … you can’t really do anything”. The participant also praised the Highland Council, the local authority, in providing extensive opportunities for professional learning, but again here noted that time constraints were the major factor in these opportunities not being taken up to the fullest extent. In terms of school culture more widely, the participant noted a diversity of extracurricular activities available, and stated his intent to lead an activity based on the Aspire Project, relating to character education, in the coming year.

Conclusion

Through the survey and semi-structured interviews, this background aims to provide an overview of the complex and nuanced views of educators in relation to peace education, and in doing so identifying potential gaps in the current teaching and learning of peace that justify the production and use of our comic, peace journal and Inner Peace workshop. Through dividing this research into several sections, a depth of potential research is sacrificed at the expense of a breadth of answers that teachers can provide, any of which can lead to further study. Thus, this research very much represents the first steps for investigating how peace is visualised in education. The results of the survey and semi-structured interview, despite being conducted on a relatively small-scale, begin to point to patterns in formal education in the UK (and particularly in schools teaching the CfE). Firstly, that there is a general appetite for teaching a broader definition of peace and Peace Education in schools, but the curriculum and initial and subsequent teacher training are not conducive to this teaching. Secondly, many of the aspects of Education for Peace, and further transrationality, are already present in schools, for example the comprehensive focus on wellbeing and the innovative and collaborative teaching methods, but that these elements are not being explicitly united under the overall banner of Peace Education.

References

- Adams, William C. 2015. “Conducting Semi-Structured Interviews.” In Handbook of Practical Program Evaluation, 492-505.

- Bajaj, Monisha. 2015. “‘Pedagogies of resistance’ and critical peace education praxis.” Journal of Peace Education 12 (2):154-166. doi: 10.1080/17400201.2014.991914.

- Bermeo, Maria Jose. 2022. “Peace Education, International Trends.” Journal: Encyclopedia of Violence:459-466.

- Brooks, Caroline, and Basma Hajir. 2020. Peace Education in Formal Schools: Why is it Important and How Can it be Done? : International Alert.

- Cremin, Hilary, Josefina EchavarrÍa, and Kevin Kester. 2018. “Transrational Peacebuilding Education to Reduce Epistemic Violence.” Peace Review 30 (3):295-302. doi: 10.1080/10402659.2018.1495808.

- Dicicco-Bloom, B., and B. F. Crabtree. 2006. “The qualitative research interview.” Med Educ 40 (4):314-21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02418.x.

- Frances, Ryan, Michael Coughlan, and Patricia Cronin. 2009. “Interviewing in qualitative research.” International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation 16:309-314. doi: 10.12968/ijtr.2009.16.6.42433.

- Galletta, Anne. 2013. Mastering the Semi-Structured Interview and Beyond. New York, USA: New York University Press.

- Synott, John. 2005. “Peace education as an educational paradigm: review of a changing field using an old measure.” Journal of Peace Education 2 (1):3-16. doi: 10.1080/1740020052000341786.

- Bevington, Terence, Nomisha Kurian, and Hilary Cremin. 2019. “Peace Education and Citizenship Education: Shared Critiques.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Citizenship and Education, edited by Andrew Peterson, Garth Stahl and Hannah Soong, 1-13. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Brantmeier, Edward. 2011. “Toward Mainstreaming Critical Peace Education in US Teacher Education.” In, 349-375.

- Cremin, Hilary, and Tim Archer. 2018. “Transrational Education: Exploring Possibilities for Learning About Peace, Harmony, Justice and Truth in the Twenty First Century.” In Transrational Resonances : Echoes to the Many Peaces, edited by Josefina Echavarría Alvarez, Daniela Ingruber and Norbert Koppensteiner, 287-302. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Dietrich, Wolfgang. 2012. “Transrational Interpretations of Peace.” In Interpretations of Peace in History and Culture, edited by Wolfgang Dietrich, 210-269. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Dietrich, Wolfgang. 2014. “A Brief Introduction to Transrational Peace Research and Elicitive Conflict Transformation.” Journal of Conflictology 5 (2):48-58.

- Hajir, Basma, and Kevin Kester. 2020. “Toward a Decolonial Praxis in Critical Peace Education: Postcolonial Insights and Pedagogic Possibilities.” Studies in Philosophy and Education 39 (5):515-532. doi: 10.1007/s11217-020-09707-y.

- Standish, Katarina, and Janine Joyce. 2016. “Looking for Peace in the National Curriculum of Scotland.” Peace Research48 (1/2):67-90.